Entrance to Etu’qamikejk Trail – a “Place Where Two Sides Meet” – by Etu’panuek (Williams Lake). View sign

The single-track trail begins just to the left of the sign.

Click on images for larger versions

NCC/HRM (Nature Conservancy of Canada/Halifax Regional Municipality) have not yet made a formal announcement about the “Etu’qamikejk Trail” in the SWP (Shaw Wilderness Park)* but the signs have been up for a few months. I have been getting questions about it, so here’s some info. about the name and the place.

– david p

Jan 14, 2025

__________

*The Shaw Wilderness Park formally opened in 2020. It is owned by HRM while NCC holds a conservation easement for the Park, an arrangement proposed in 2016 after the land came up for sale. See Williams Lake Conservation Company: Halifax’s New Shaw Wilderness Park for details.

In June of 2022, I was asked by Doug van Hemessen of the Nature Conservancy of Canada to suggest a name for the single track trail that begins at the east end of Etu’panuek just by the little beach/sitting area close to the dam.

In June of 2022, I was asked by Doug van Hemessen of the Nature Conservancy of Canada to suggest a name for the single track trail that begins at the east end of Etu’panuek just by the little beach/sitting area close to the dam.

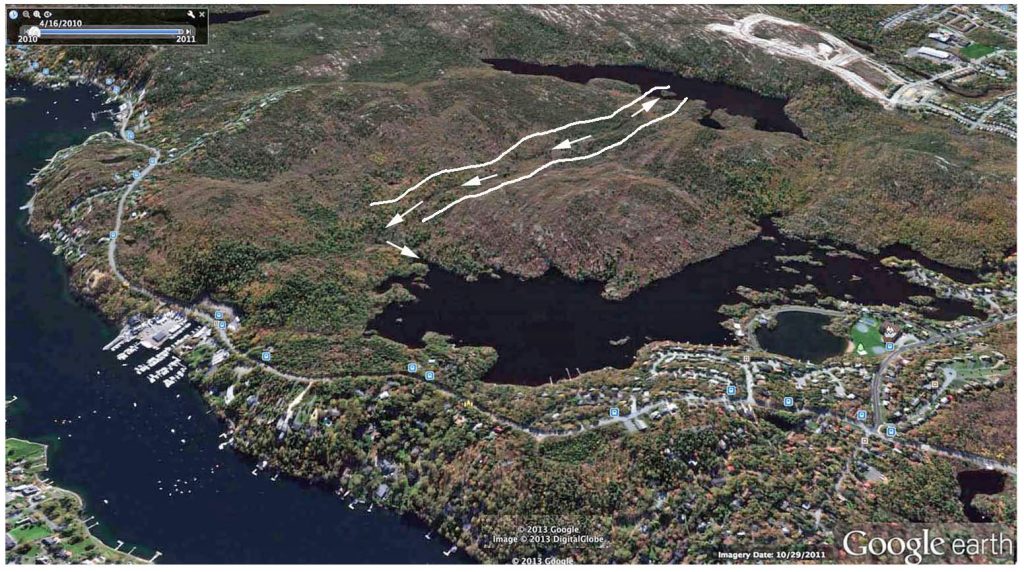

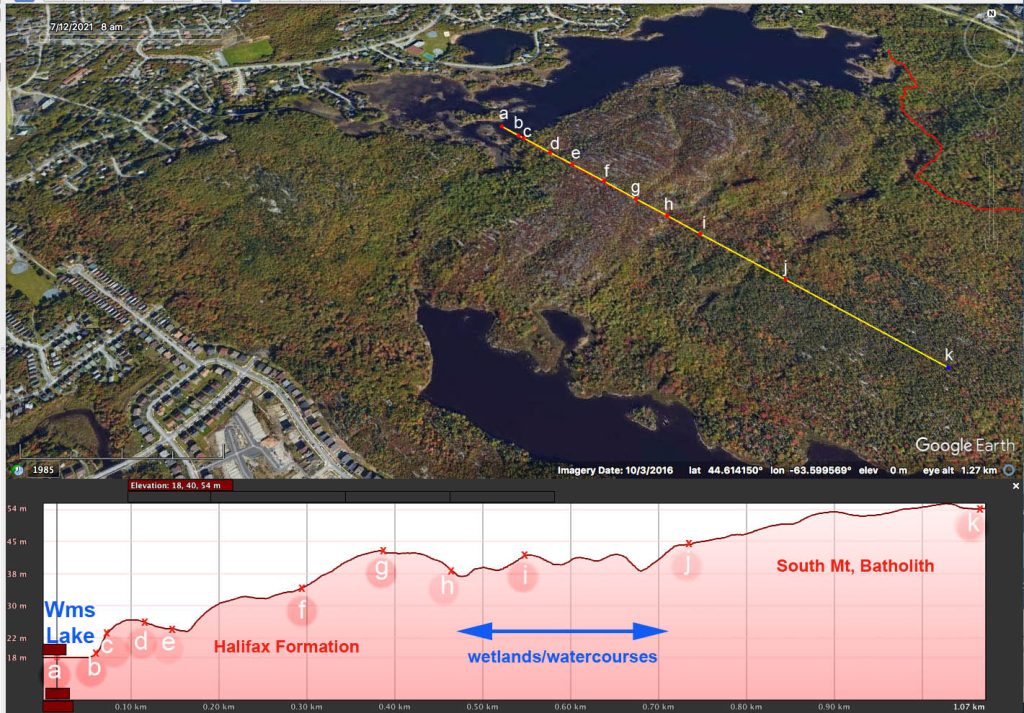

From there, the trail proceeds south across a rough rocky piece of “Meguma Terrain”, tracks southwest along a geological contact zone/wetland & watercourse corridor and then takes a turn to the southeast proceeding uphill to the Jack Pine/Broom Crowberry Barrens on granitic rock of the South Mountain Batholith:

Etu’qamikejk Trail. Trail Signs at white dots. Trail route generated on Google Earth from a NCC kml file. Distance between the arrows, approx 746 m as the crow flies, 1025 m walking (Google Earth estimate).

Etu’panuek, the Mi’kmak name for Williams Lake, from Ta’n Weji-sqalia’tiek, Mi’kmaw Place Names

View Map with elevation profile.

Click on image for larger version

It’s a traditionally traversed route which NCC cleaned up and marked out with unobtrusive red tags on trees while they eliminated or otherwise discouraged use of splinter trails. A few minutes in, and one is in a very peaceful, natural place, well away from urban life.

Walquqmikek – gully. On the Etu’qamikejk Trail, Aug 16, 2022. View short video

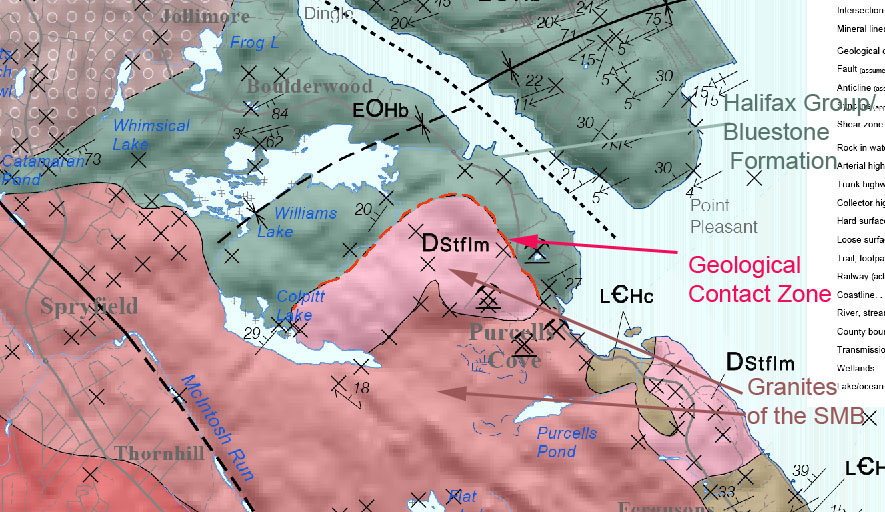

My immediate thought about a trail name was that it should be a Mi’kmaw name. And I was thinking it could be a name that relates to a prominent landscape feature: a geological contact zone – a place where “two lands meet” – between rocks of the Halifax Formation in the Meguma Terrain* whose origin goes back 500 mya (million years ago) to the edges of the super-continent Gondwana; and rocks of the South Mountain Batholith (SMB) which are “intrusive granites” formed circa 380 mya, all further sculpted by successive glaciations, the last ending only circa 12000 ya.[1]

*The name “Meguma” was applied to this terrain by J.E. Woodman in 1902, to acknowledge its occurrence in Mi’kmaki territory. [2]

Map showing bedrock geology in the area of Willams and Colpitt Lakes. Click on image for larger version with legends, or view Source Map (NS Gov 2014)

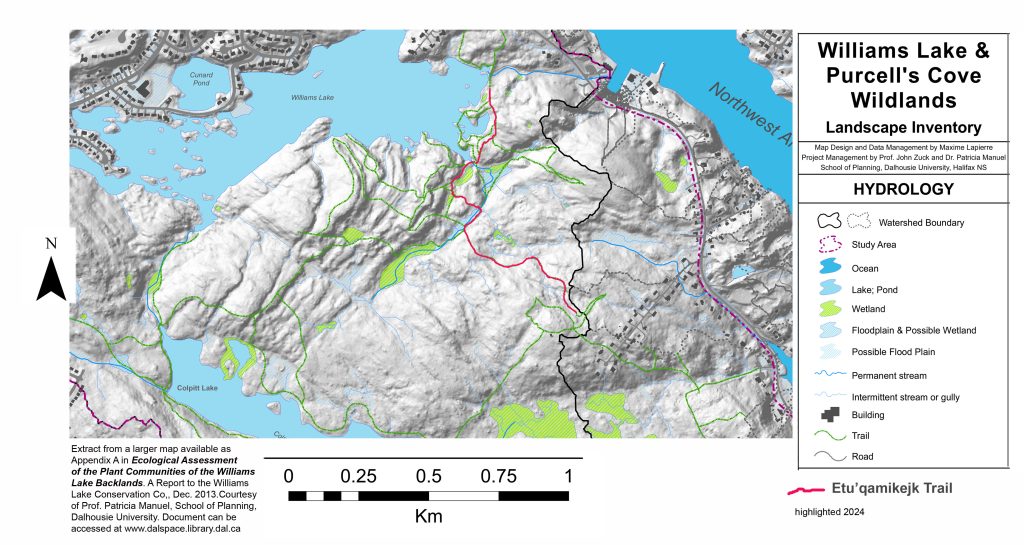

The Halifax Formation (variously described as a Group or a Formation) is exposed to the north of the contact zone, and the SMB to the south. The low-lying interface is today a major wetland/watercourse corridor that is highly significant locally for it’s biodiversity and hydrological functions.

Lidar-based map showing hydrological features in the area of Willams and Colpitt Lakes. Extracted from Williams Lake & Purcell’s Cove Wildlands Landscape Inventory Map by Dalhousie University School of Planning group, provided courtesy of Patricia Manuel. View full Map

Google Earth perspective of Williams Lake Backlands approached from the northeast & direction of water flow along the contact zone between Williams and Colpitt lakes.(Appendix A Map 4 in Ecological Assessment of the Plant Communities of the Williams Lake Backlands by N. Hill and D Patriquin, 2014. View Contact Zone Williams to Colpitt Lake (page on this website) for more about the Contact Zone. View Map with Elevation Profile. Click on image for large version.

The Etu’qamikejk trail traverses an unusual landscape with vistas varying from serene to spectacular, adorned here and there with nature’s sculptures in the form of glacial erratics, whalebacks, boulder fields and snags (old dead trees). The palette changes with the seasons, most dramatically in mid-fall when the huckleberry leaves turn fire-engine red.

I was very familiar with ‘The Language of this land, Mi’kma’ki’ (Cape Breton University Press, 2012; now Nimbus Publishing) co-authored by anthropologist/educator Trudy Sable and Mi’kmaw orthographer Bernie Francis. The book describes how the “rhythms, sounds and patterns of the language are inextricably bound with the seasonal cycles of the animals plants, skies, waterways and trade routes” and how “the ancient languages of Eastern North America are reflected in the language and cultural expression of its indigenous peoples, the Mi’kmaq.”

It’s a wonderful, enlightening read – and re-read – which made a big impression on me. I was particularly intrigued with the name and discussion, pp 68 & 69, of Taqamiku’jk, the “causeway”, “Boars Back”, “spine’ or “little crossing place” that runs from Parrsboro to Cape Chignecto as I have an interest in the natural history and human history of that area.* I wondered whether that name/context could apply to the contact zone/water corridor in the SWP.

* See www.parrsboroshoredays.ca

So I thought, why not, I will ask Trudy Sable and Bernie Francis – who I then knew only through the book – for their thoughts about my thoughts.

The immediate response was that they would like to walk the trail!

So on a beautiful day in late August 0f 2022 we did just that. During the walk, we discussed various landscape and ecological features we were seeing and the related processes; Bernie was continually verbalizing names for these features. It didn’t stop there. Later he thought a lot more about the features and of what would be the most appropriate expressions to describe them. We held several meetings to discuss it all.

On Nov 15, 2022, we submitted a report on “Proposed Mi’kmaw names for trail in the Shaw Wilderness Park, and some related landscape features” to NCC/HRM. In that report, Bernie proposed these names for the trail and some related landscape features:

The Trail name would be “Etu’qamikejk Trail”*

The words in Mi’kmaw are verbalized by Bernie in a recording in the order listed below:

- Kuowa’qmikt – place of pine (pine grove).

- Etu’qamikejk – two sides meet, or land on either side (in this case two lands separated by a gully)

- Paqtaqmikt – forest

- Walquqmikek – gully

- Skipaqmikt – swamp

- Kun’tewa’qmikt – rocky place, in reference to the Backlands as a whole.

_____________________________

*Said Bernie in response to a request to spell Etu’qamikejk phonetically:

“It’s: “Eh doo hum i gehjk”. The k attached at the end is the locative. It’s a post-position in this case meaning, in or at.”

“I’m happy to report that the Etu’qamikejk Trail signs have been installed at the bottom and top of the trail at the Shaw Wilderness Park.

Thanks for your time and patience with this. Some photos attached.” – Doug van Hemessen to Trudy S, Bernie F, and David P. Aug 28, 2024

Click on image for larger version

NCC/HRM accepted the names. Over the ensuing year, the related signage went through a few iterations, discussed between NCC, HRM and ourselves (Bernie F, Trudy S and David P)

On Aug 28, 2024, we received word that trail signs had been installed at the bottom and top of the trail (right).

At this point we don’t know whether or when there will be more followup, e.g. related to “further interpretive signs eventually along the trail” that would highlight the related landscape features.

Regardless, going forward we can continue to enjoy this wonderful landscape and now, to apply these names.

Perhaps by practicing the pronunciation of the names as we walk the landscape, we can begin to understand how the “rhythms, sounds and patterns of the Mi’kmaw language are inextricably bound with the seasonal cycles of the animals plants, skies, waterways…” and become ever better stewards of the land in the process.

Thanks to Bernie and Trudy for helping us in this endeavor. Thanks to the Mi’kmaw people who stewarded the lands of Mi’kmaw Territory for thousands of year and continue to do so. Thanks to NCC and its many supporters, to HRM, WLCC (Williams Lake Conservation Co.), Allan Shaw and to the many past and ongoing and future volunteers for caring so much about the land now protected as the Shaw Wilderness Park and for all of its inhabitants.

– David P, Jan 2, 2025

Notes

1. On the Geology: Racheal Groat provides a succinct, referenced summary of the Geological History of Purcell’s Cove written for non specialists in pages 17-23 of her Bachelor of Community Design Honours Thesis: Interpretation Planning for Purcell’s Cove Quarries (Rachael Groat, 2016). See also her Appendix A: Geologic History Timeline p. 43. The Geological History section begins ” The geology of Purcell’s Cove is special because it is the contact between the granite of the South Mountain Batholith and the slates of the Halifax Group.” The contact zone she cites is is the southeastern extension of the contact zone that the Etu’qamikejk Trail crosses. View View also:

– www.backlandscoalition.ca/Natural History/Geology

– www.backlandscoalition.ca/Natural History/Specific Areas/Contact Zone Williams to Colpitt Lake

2. 1. The name for the Meguma Terrain was proposed by J.E. Woodman (1902) in his Harvard University PhD thesis Geology of the Moose River district, Halifax County, Nova Scotia; together with the pre-Carboniferous history of the Meguma series. “To avoid duplication and confusion in the literature, Woodman (1902) proposed using local Mi’kmaq terms rather than geographic terms for unit designation. He assigned the names ‘Lampok’ (which means bottom) and ‘Seskoo’ (which means mud) formations to the designated lower quartzite and the upper slate divisions, respectively [now recognized as the Goldenbille and Halifax Formations respectively]. He also placed these formations into the Meguma series. Meguma is also a Mi’kmaq word, root of the native term for their tribe, and hence appropriate for rocks occupying so large a part of Nova Scotia (Woodman 1902).” – From C.E. White 2010. Stratigraphy of the Lower Paleozoic Goldenville and Halifax groups in southwestern Nova Scotia Atlantic Geoscience Vol. 46, pp 136 – 154.

Other than the Woodman (1902) and White (2010) references cited above, there appears to be little, if any, documentation about the origin of the name Meguma for this geological terrain. In regard to the names assigned by J.E. Woodman in his 1902 thesis (not available digitally), as cited by CE White (2010), Bernie Francis had this to say:

“Two words should be corrected: Bottom (of water) should be spelled “lampo’q.”, not ‘Lampok’

“The word for mud should be “sisku” not ‘Seskoo’ .

“In regard to Woodman’s use of the term “Meguma”, I’m guessing he heard Mi’kmaq but did not hear the velar, q well enough, or, didn’t know how to represent it using the Roman orthography. The q in Mi’kmaw is sometimes simply referred to as the guttural sound. German, Arabic, French, Gaelic and other languages all have it.

“Surprisingly though, the NB dialect of Mi’kmaw uses a glottal stop (sometimes referred to as glottal catch) so-called bc it involves the glottis. Where we use the velar, they’ll use the glottal stop, but not 100% of the time. Some English speakers use the glottal stop for words like “bottle.” They say something like “ba ‘el” with the apostrophe representing glottal catch and the following e is sounded like a schwa.

“Readers may remember the movie, My Fair Lady where a linguist works on the speech of a cockney English speaking young lady. One of the linguist’s problem is his attempt at ridding her of the glottal catch in sentences such as: You got a daughter? Which comes across as “You go’ a daugh’ er. The t is often replaced by a catch.”

A few more photos illustrating the Contact Zone/Wetland & Watercourse corridor, and major rock types

View at the base of the highly metamorphosed and folded Halifax Group outcrops in the Contact Zone, looking north; boulder field in foreground. Photo on Oct 22, 2014. This area burned in May of 2012.

Jack Pine/Broom Crowberry barrens on granitic bedrock in October. Black huckleberry leaves in their “fire-engine red” stage, just before they drop. A patch of low growing Broom Crowberry can be seen in the foreground

Elevation Profile generated on Google Earth for a virtual transect from Etu’panuek (Williams Lake), across the folded rock face of the Halifax Formation, across the area of wetlands/contact zone and up onto the granite of the South Mt. Batholith. The reddish hue (crossed by e to g above) is due to the fire-engine red coloration of black huckleberry leaves just before they drop (Google Earth image dated Oct 3, 2016).

For more about the natural history of the area, see

– Natural History

A section of this website

– Ecological Assessment of the Plant Communities of the Williams Lake Backlands

A report by N. Hill and D. Patriquin to the Williams Lake Conservation Co. Feb 12, 2014. (108 pp) Available on Dalspace

– Shaw Wilderness Park Field Trip

Report on an excursion by the Halifax Field Naturalists, led by Sean Haughian of the NS Museium of Natural History, 8 June 2025, by Brian Bartlett

—–

List of Mi’kmaw names cited above

To print, carry on your next walk on the Etu’qamikejk Trail