Drafting (dp July 2022)

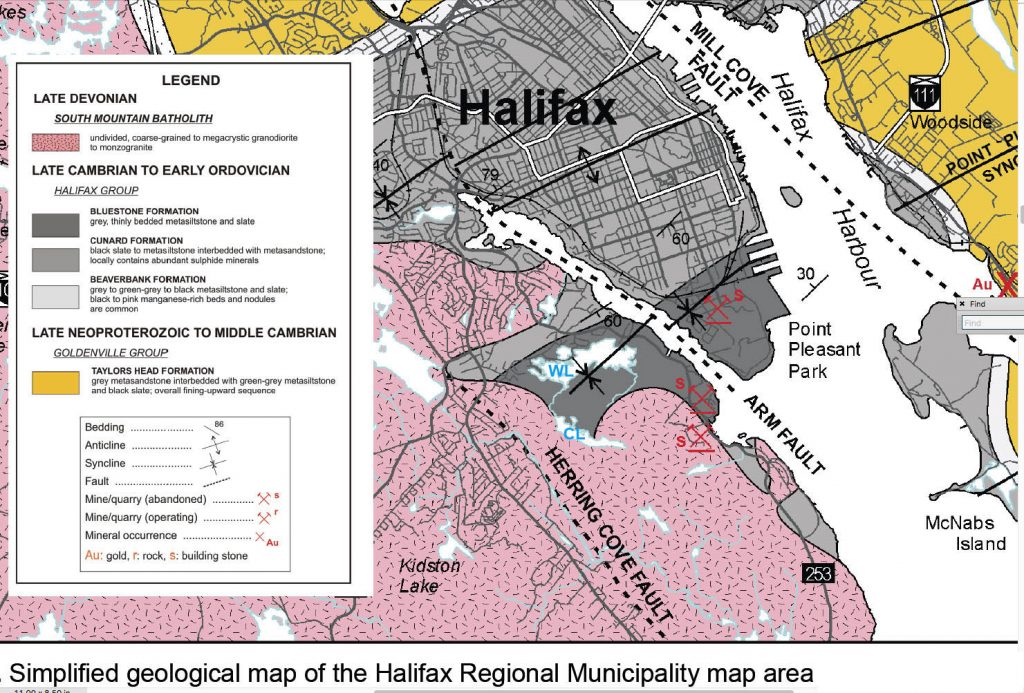

A neat piece of Nova Scotia’s geological history can be seen in the “Williams Lake Backlands” (most of which is now in the Shaw Wilderness Park): a contact zone between between the granitoic rocks of the South Mountain Batholith and the black slates and siltstones of the Halifax Formation. It is well exposed between between Williams and Colpitt Lakes.

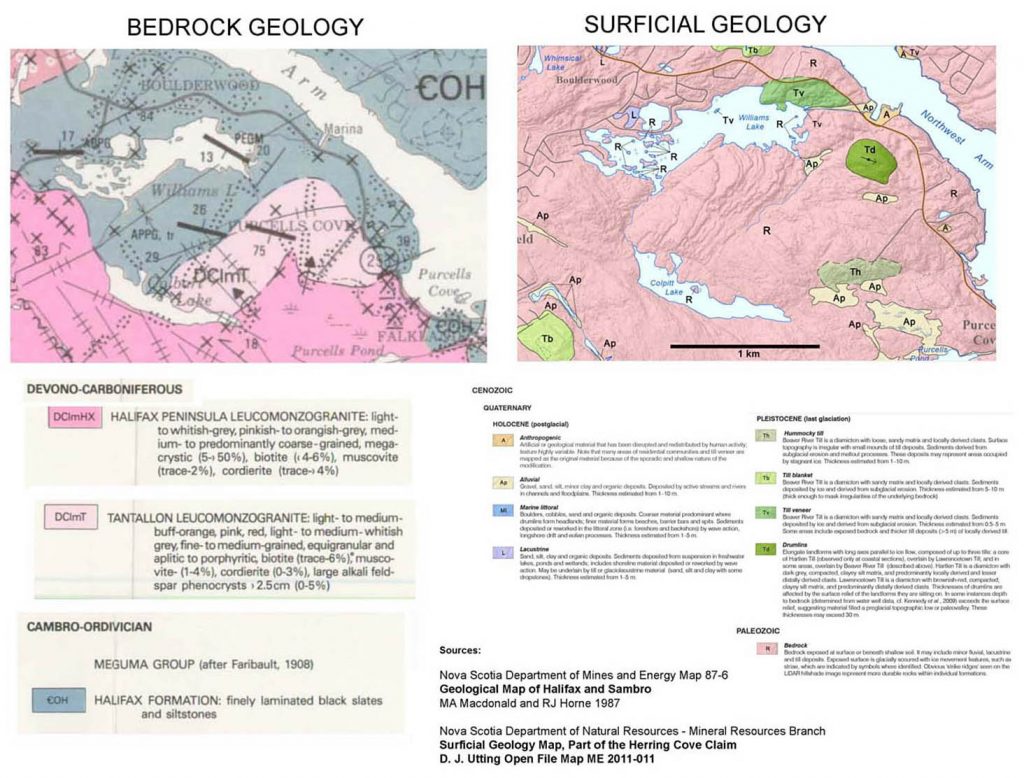

Bedrock Geology (left) and Surficial Geology (right) in the Williams Lake Backlands (Shaw Wilderness Park). From Nova Scotia Government Maps (Appendix A Map 4 in Ecological Assessment of the Plant Communities of the Williams Lake Backlands by N. Hill and D Patriquin, 2014.) Williams lake is the larger of the two lakes shown, Colpitt Lake lies to the south of Williams Lake. Click on image for large version

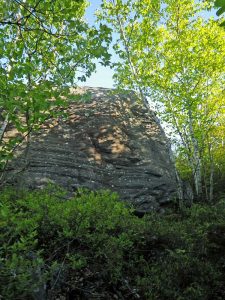

To the northeast of the contact zone between Williams and Colpitt Lakes, outcroppings of highly folded and metamorphosed rocks of the Halifax Group Bluestone Formation rise steeply and from the highest points afford a panoramic views of Williams Lake. To the southwest, rising less abruptly, are the granites of the South Mountain Batholith.

“Despite sounding like something out of Harry Potter, a batholith is a type of igneous rock that forms when magma rises into the earth’s crust, but does not erupt onto the surface. The magma cools beneath the earth’s surface, forming a rock structure that extends at least one hundred square kilometers across (40 square miles), and extends to an unknown depth.” – USGS Earthword: Batholith

View at the base of the highly metamorphosed and folded Halifax Group outcrops in the Contact Zone, looking north; boulder field in foreground. Photo on Oct 22, 2014

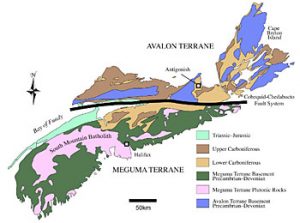

Generalized geologic map of Nova Scotia.

From Schenk et al., Figure 2; click on image for

the article and a large version of this map.

The South Mountain batholith formed circa 380 million years ago. It extends “in an arc from Yarmouth to Halifax and outcrops over an area of 10 000 km2…the largest body of granitoid rocks in the entire Appalachian system” (NSM); as it pushed its way into the older sedimentary rocks of the Meguma Supergroup above, it heated and folded them. Successive glaciations over the last 3 millions scraped off the softer rock above the batholith, eventually exposing the harder granites and revealing the contact zone. (See references below for more about the fascinating geological history of Nova Scotia.)

Areas in the vicinity exposed bedrock on both the granitoic and the Halifax Formation bedrock support the “Globally Rare and Nationally Unique” Jack Pine Broom Crowberry communities, a type of fire-adapted and fire dependant pine barrens. Some have burned within the last dozen or so years. The oldest unburned stands are 60+ years old. They are most striking in the fall when the black huckleberry turns fire engine-red. Repeated fires at intervals of 50+ years are a natural occurrence in these areas.

Jack Pine-Broom Crowberry barrens on granitoic bedrock in October. The red shrubs are black huckleberry. A patch of low growing Broom Crowberry (green) can be seen in the foreground

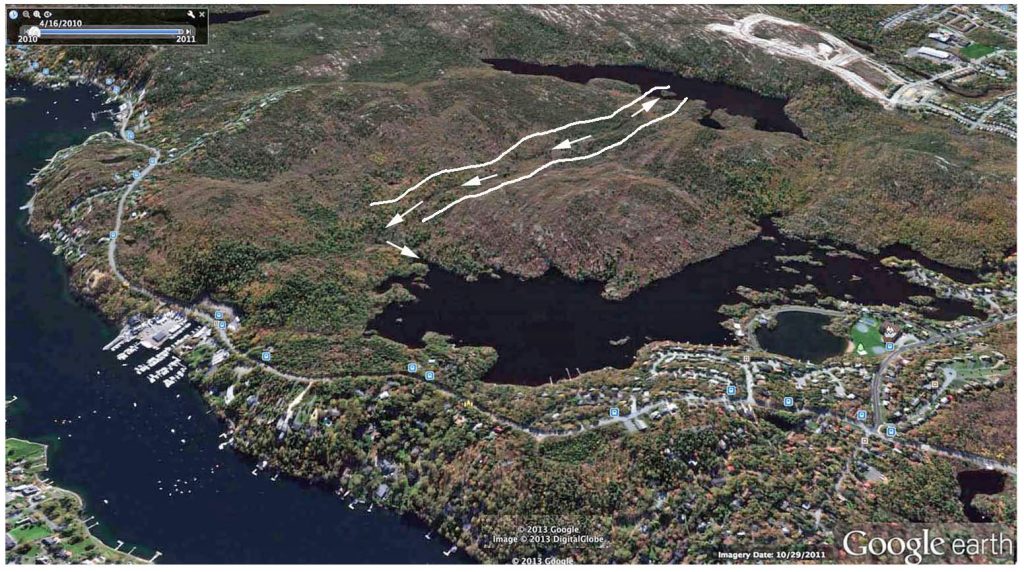

A major area of water storage and movement occurs along the low lying contact zone between Williams and Colpitt Lakes. The water moves below- and above-ground and through wetlands; most of it drains into Williams Lake but close to Colpitt Lake, into Colpitt Lake.

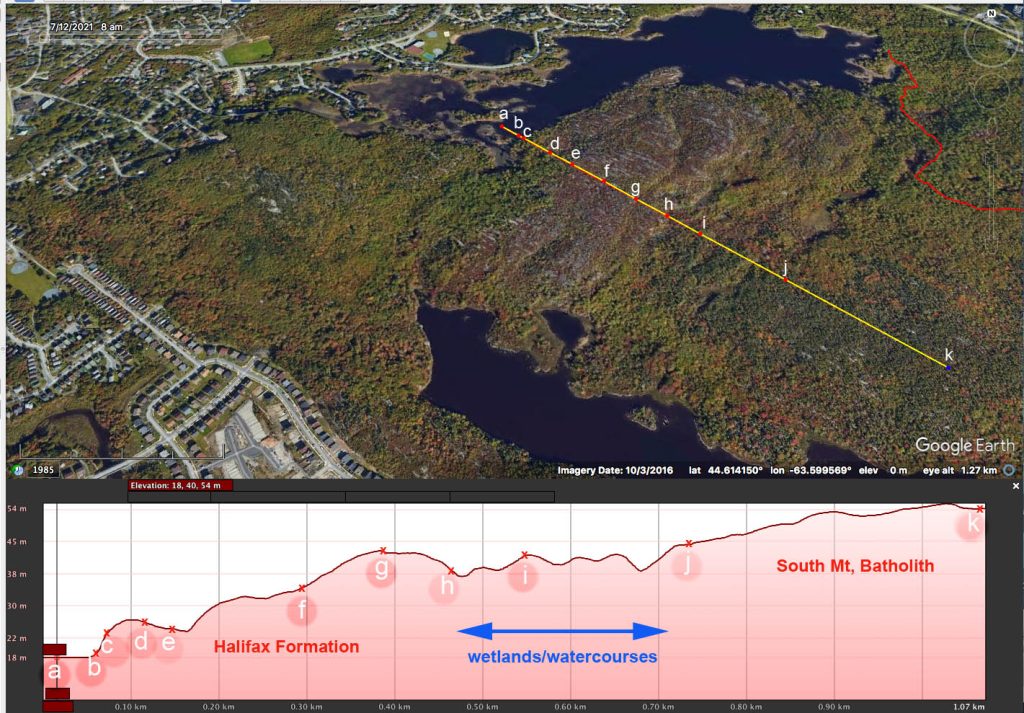

Google Earth perspective of Williams Lake Backlands approached from the northeast & direction of water flow along the contact zone between Williams and Colpitt lakes.(Appendix A Map 4 in Ecological Assessment of the Plant Communities of the Williams Lake Backlands by N. Hill and D Patriquin, 2014. Click on image for large version

Elevation Profile generated on Google Earth for a virtual transect from Williams Lake, across the folded rock face of the Halifax Formation, across the area of wetlands/contact zone and up onto the granite of the South Mt. Batholith

Boulder fields with massive, angular black boulders occur towards base of the outcrops and ‘spill’ into wetlands. These boulders were deposited as the last glaciers in the area retreated; the rocks are so angular they look to the untrained eye (mine)as they might have been cut from a quarry.

Comment on Boulder Fields: I sent photos of boulder fields in the Backlands to two geologist friends and was referred to John Gosse of the Dalhousie Department of Earth Sciences. he commented:

They do look like small localized felsenmeer (sea-of-rocks) fields, but the slope suggests that there may be a different genesis. Without being there it is difficult to be certain, but these kinds of boulder zones are common in glaciated regions. They form either subglacially or, more commonly, along the sides of retreating ice margins. Specifically this looks like a lateral meltwater channel, formed along the side of an ice lobe, with the water flowing downslope. The meltwater stream would have removed the finer sediment and left the larger boulders alone. The angularity of the boulders is also interesting. This is typical in these situations, where the stream was short lived and did not have the energy to round the boulders’ edges. On the other hand, boulders that are transported some distance by glaciers will also lose their angularity (depending on hardness and distance of course). That these boulders appear so angular suggests to me that they may not have been transported very far subglacially (though they were certainly covered by ice during the last major glaciation), and therefore may indicate a zone of the ice sheet that was cold-based (stuck to the substrate for most of its history, instead of sliding and transporting the boulders a long way).

As water moves towards Williams Lake from the ‘Great Wetland’ it goes entirely below rough rocky ground in pine/oak forest for about 100 meters and then surfaces in a series of treed and sedge-and fern-lined wetlands until it reaches ‘The Gully’. There it spills down a steep slope below massive boulders in the shade of oaks and striped maples that hang over the gully. Evergreen polypody ferns adorn some of the boulders. From The Gully, water moves as slower moving stream through a large floodplain, through a fen and then converges on a fast moving stream, and finally into a little bay on Williams Lake where beavers are always busy.

On the Colpitt end, water moves off steep slopes though boulder fields, a serene floodplain forest and by a large lakeside fen into the beautiful, boreal-like Coplitt Lake; the lake is well hidden from the settled landscape beyond by a steep forested slope that rises above the lake.

Smaller and larger erratics are scattered throughout this landscape. It is a mosaic landscape with many flavours and moods, and little nooks where one can not see or hear any sign of the busy world outside. Places to truly escape.

Smaller and larger erratics are scattered throughout this landscape. It is a mosaic landscape with many flavours and moods, and little nooks where one can not see or hear any sign of the busy world outside. Places to truly escape.

From WLB Summary

The WLB present a mosaic of landscapes and plant communities associated with high variability on a fairly small scale in the topography, depth of soil/till, drainage and surface water storage and in the ages since disturbance of the associated plant communities. That variability in turn is related to the presence of glacially scoured hard granite outcrops of South Mountain Batholith, outcroppings of highly folded and metamorphosed Halifax Group black slates and siltstones of the Meguma Supergroup, a contact zone between the two rock types, and glacial till. Overall, the plant communities are those of nutrient-poor, acidic environments and of fire-, wind-, and pest-driven disturbance regimes within a moist temperate, coastal region. Exotic (non-native) species are found only close to roads and houses at the edge of the WLB. These are “old process” plant communities with a high degree of ecological integrity.

Introduction to the Geological History of Nova Scotia

In the Natural History of Nova Scotia, Vol 1 (1996) under Topic 2 (T2): Geology. Nova Scotia Museum/Nimbus Publishing

Paleozoic History of Nova Scotia A Time Trip to Africa (or South America)

Paul E. Schenk, Thomas Lane and Lyndon Jensen On www.dal.ca, Dept of earth & Environmental Science

Nova Scotia Field Guide

Arthur D. Storke Memorial Expedition, 2012. Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences, Columbia University “This guide was prepared following the 2012 Arthur D. Storke Memorial expedition to Nova Scotia, with broad overviews of Nova Scotian geology and detailed itineraries and descriptions of individual outcrops visited. Our hope is that this guide can serve as a blueprint for future trips to Nova Scotia. For faculty and students in the northeastern United States, outstanding outcrops detailing the Phanerozoic history of continental collision and rifting are not that far away. Nova Scotia is waiting.

Geological Notes

The Backlands are a glacially sculpted terrain, with features such as erratics, whalebacks and drumlins. Granite and “bluestone” metamorphic rocks were once quarried in Purcell’s Cove, for buildings and fortifications. Geologist Marcos Zentilli prepared these notes for a set of Jane’s Walks into the Backlands on May 3, 2014.

Long-lived association between Avalonia and the Meguma terrane deduced from zircon geochronology of metasedimentary granulites

J. Gregory Shellnutt et al., 2019. Nature Scientific Reports volume 9, Article number: 4065 (2019) “The Acadian Orogeny of the Northern Appalachians was caused by accretion of the peri-Gondwanan terranes Avalonia and Meguma to the eastern margin of Laurentia during the Devonian. The lithotectonic relationship between Avalonia and Meguma prior to accretion is uncertain.Radioisotopic dating of detrital zircons from metasedimentary granulite xenoliths from the structural basement to the Meguma terrane indicates that Avalonia and Meguma were proximal and likely contiguous as they transited the Rheic Ocean…The implication is that Avalonia and the Meguma terrane jointly transited from Gondwana.”

Tracing garnet origins in granitoid rocks by oxygen isotope analysis: examples from the South Mountain Batholith, Nova Scotia

J.S. Lackey et al.. 2011 The Canadian Mineralogist 49(2):417-439 “Garnet in Nova Scotia’s peraluminous South Mountain Batholith (SMB) displays diversity in its texture and composition that has challenged a comprehensive explanation of its origins. In this study, we have employed oxygen isotope analysis to “fingerprint” magmatic, peritectic, and xenocrystic SMB garnets to take advantage of contrasting delta(18)O of SMB and metasedimentary country-rocks and the slow rates of diffusion of oxygen in garnet…”

Last Days of an Urban Wilderness? Williams & Colpitt Lakes Backlands

Photos from hikes with Halifax Field Naturalists (August 25th, 2012) & Williams Lake Conservation Co. (June 1st, 2012) Photos by David Patriquin. Written at a time when it looked as though these lands would be developed.

Geology of the Halifax Regional Municipality,Central Nova Scotia

White, C. E., et al., 2008. In Mineral Resources Branch, Report of Activities 2007; Nova Scotia Department of Natural Resources, Report ME 2008-1, p. 125-139.

Structural Geology and Deformation Of The Meguma Group At The Northeastern Contact Of The South Mountain Batholith, Halifax Area, Nova Scotia

Bhatnagar, Pradeep. Report for BSc in Earth Sciences, Dalhousie University 1997. Supervisor: Dr. Nicholas Culshaw. Available on Dalspace, 257.9Mb. “Structural mapping and petrographic analyses were conducted to document the structural geology and deformation of the Meguma Group country rocks adjacent to the Halifax Pluton of the South Mountain Batholith (SMB) near Halifax, Nova Scotia. Intrusion of the Devonian South Mountain Batholith caused local deformation and metamorphism of the Cambrian-Ordovician Meguma Group. The mapped portion of the SMB-Meguma contact of this study has been subdivided into two parts based on the style of emplacement. Passive emplacement, occurring south of the Williams Lake area, is characterized by regional structures preserved up to the SMB contact (e.g., bedding, cleavage, bedding-cleavage intersection lineations, and minor folds), stoping, and dyking. Evidence that suggests active emplacement, occurring north of the Williams Lake area, includes: the Kearney Lake Transverse Anticline, deflection of bedding…”

From the Introduction: “The South Mountain Batholith (SMB) is the largest intrusive granitoid body in the Appalachian Orogen. The SMB is a large, approximately ca 3 70 Ma, peraluminous, epizonal intrusion occurring within the Meguma Terrane. The Meguma Terrane is the most outboard terrane of the Appalachian Orogen (Williams and Hatcher, 1983). The Meguma Terrane is dominated by the Meguma Group, a conformable sequence of Cambrian-Ordovician metagreywacke and metapelite. Studies have suggested that theSMB is a post tectonic intrusion (Clarke and Chatterjee, 1988) emplaced after deformation associated with the Middle Devonian Acadian Orogeny, responsible for the formation ofNE-SW trending regional folds. However a more recent study by Benn et al. (1997), suggests a syntectonic (syn-Acadian) emplacement model for the SMB.

“The emplacement of the SMB resulted in local contact metamorphism and deformation of the surrounding Meguma country rocks. This thesis describes structural, metamorphic and microscopic features observed at a portion of the northeastern SMB(Halifax Pluton)-Meguma contact and suggests an emplacement model for the SMB in this area.”