Contributed by David Patriquin

Update May 28, 2023: Out-of-control fire in Upper Tantallon Area, All of HRM under Fire Ban. View The Coast

———-

Fire scarred white pines. Left by eastern corner of Williams Lake. Middle and right: on the barrens by the Osprey Trail.

Click on images for larger versions.

On the last weekend in April, I participated in two walks in the Backlands in which we encountered fire-scarred white pines.

The first was on a birding walk with Fulton Lavender in the Shaw Wilderness Park. As we moved on the single track trail by the eastern corner of Williams Lake, we passed by a large white pine with a prominent fire-scar at its base; at least I had always assumed that’s what it was. There was some discussion about whether it might have been caused by a lightening strike on that tree rather than associated with a forest fire.

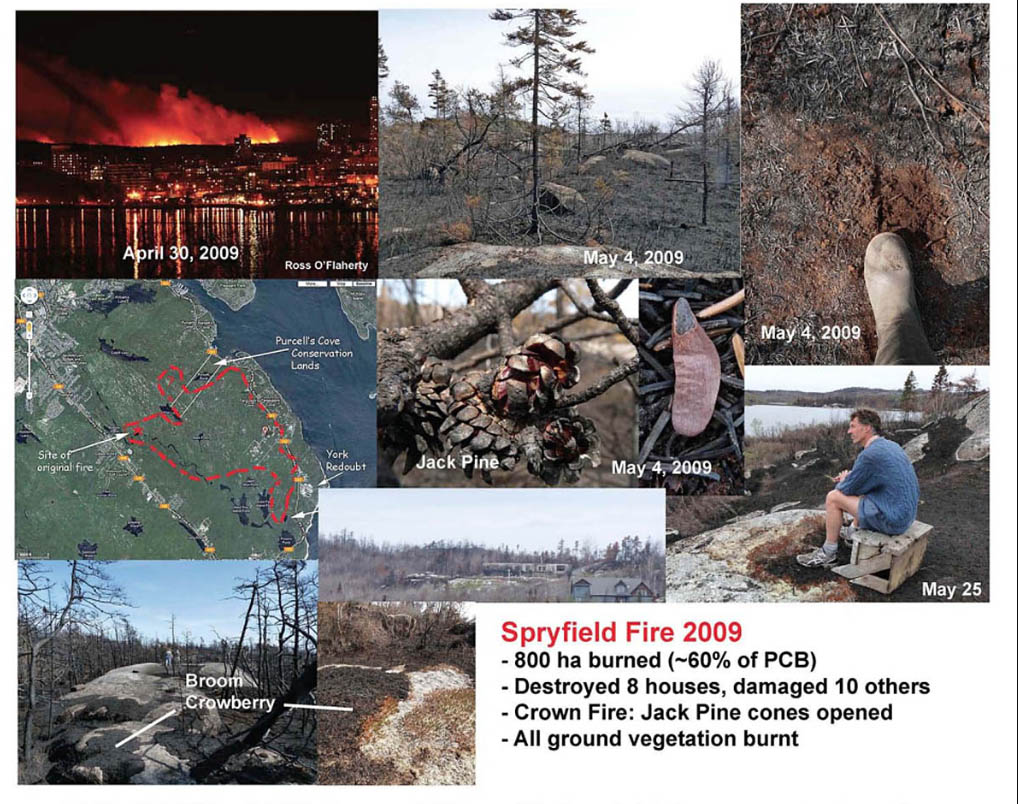

The next day I participated in a NS Wild flora Society walk on the Osprey Trail (McIntoshRun trails). About a kilometer in, there was a lone, tall white pine on landscape that burned over in 2009; it was about 50 m distant. The deciduous trees and bushy ground vegetation had not yet leafed out and we spotted a fire scar at its base. That fire scar pretty well had to be from the 2009 Spryfield fire and lends support to the interpretation of the scar on the Williams lake area pine as a fire scar. So does the description of fire scars in the (see below)

When might the fire scar at the Williams Lake site been formed? Residents in the Williams Lake area cite 1964 (59 years ago) as the year of a fire in the backlands that extended into the forest on the eastern side of Williams Lake, sparing only the tall red and white pines and some oaks that we see today towering above younger forest. All 3 of these tree species can withstand surface fires once they are older and bark has thickened sufficiently.

How old would the fire scarred pine have been when the fire occurred? There is a recently sawed, roughly 2.2 ft diameter stump of a white pine located close to the parking lot for the Shaw Wilderness ParkPark. I counted 115 growth rings on it; add a few years for the original seedling to reach the height of the stump, and allowing for some uncertainty in a few the rings, I estimate its age as 115-120 years. The tall fire scarred pine at the east of the lake was probably in the same cohort; so the age at which it was burned is estimated as (115 or 120) – 59 = 56-61 years, old enough to have withstood surface fires (Guyette and Day, 1995).

Like the Jack Pine-Broom Crowberry communities that occur towards the edges of exposed outcrops that occur all through the Backlands, those fire scarred white pines are reminders that the Backlands at large is an exceptionally fire-prone area.

Images from areas burned during the Spryfield Fire of 2009. View details

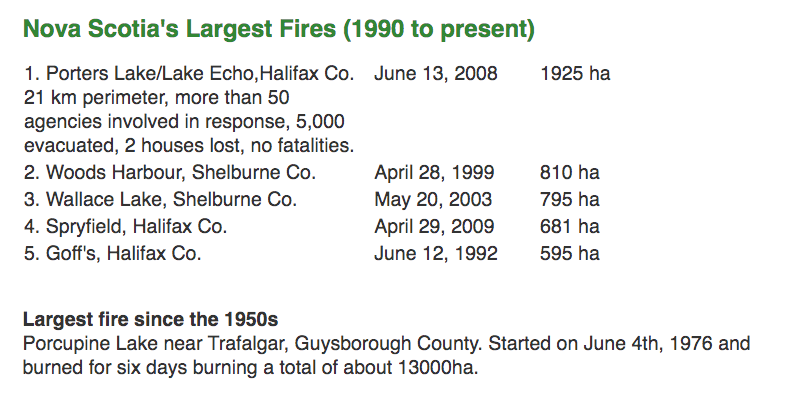

Indeed, the Spryfield fire of 2009 – which was restricted to the Backlands and burned over half of the Backlands – was one of the largest in the province in in recent years.

Fire Season: April to October

Fire season in Nova Scotia is considered to be April to October. Generally we expect May to be the busiest fire season.

The frequency of fires changes throughout the fire season (April to October). May is usually the busiest month due to the fact that vegetation hasn’t fully come out of dormancy and begun to grow. The moisture content of these fuels is low, making them are more flammable. This is known as a “before green up” condition – NRR: Wildfire (accessed 15May 2022)

“Fire break on the Seven Mile Lake fire made by heavy equipment to remove all combustible material down to bare mineral soil. (Donna Crossland)” View CBC report (Aug 17, 2016)

With increasing droughtiness during our summers and sometimes well into fall, we are seeing more fires in the summer and fall seasons. These later fires can be more damaging than in the spring and much more difficult to control. Spring fires, while they may burn all above-ground vegetation, burn only the very surface of the soil as most of the soil is still water saturated. But following prolonged drought in late summer/fall, the soil can dry out right down to the bedrock; then a forest fire will burn organic materials well below the soil surface and can continue to smoulder below-gound even after the fire above-ground has been extinguished.

So we need to be on the lookout for fires all through the fire season (April to October), and especially in the Backlands.

Advice to hikers that I heard recently on CBC was to check the fire index before setting out, and if you see a fire to note its location, report it ASAP, and get out as quickly as possible.

More nuanced and very useful, potentially life-saving advice on what to do if you see a fire is offered by Katie on Outdoors and On the Go; or view the text only here.

Needless to say – 0r perhaps it needs to be said (re: photo at left): setting fires of any sort in the Backlands should be a no-no.

The photo shows campfire residues on Jack Pine-Crowberry barrens, viewed on May 2, 2016. As well as being immediately hazardous – the campfire was set in the most flammable area of the Backlands and at a time of year especially prone to fire – the not-cleaned-up residues convey the message: “It’s OK to have campfires here”. It isn’t!

Wishing everyone Safe Travels in the Backlands, Anytime!

– david p

SOME RELATED PAGES ON THIS WEBSITE

– Fire Scars & Old Trees

– Fire Ecology

– JP-Crowberry Barrens & Fire Mgmt

– Surviving a Wildfire while Hiking

– HRM & NS Fire Links

SOME RELATED POSTS ON THIS WEBSITE

– Recent fire and fire management in the New Jersey Pine Barrens: a model for the Backlands? 12Jul2022

– Mapping forest fire risk in the Eastern Chebucto Peninsula Backlands (Post Apr 29, 2021)

RECOGNIZING FIRE EVIDENCE

E.A. Johnson, S.L. Gutsell, Fire Frequency Models, Methods and Interpretations Advances in Ecological Research, 1994

The most often used evidence of past fire is fire scars. Although fire scars may seem easy to recognize, they can be confused with scars resulting from other causes (e.g. Mitchell et al., 1983) such as those shown in Table 2. If the origin of a scar is in question, it should not be used. Fire scars always form at the base of the tree, usually in a triangular shape. They often form near the boundaries of a burn in active crown fires, but this is not always the case in ground fires or passive crown fires. Active crown fires have a fire front which is a wall of flame extending into the crowns, whereas passive crown fires occur when a ground fire extends into the crown and burns a single tree (Van Wagner, 1977). Trees with multiple fire scars often, but not always, have charring on the older scar faces and consequently could provide evidence that the most recent scar was caused by fire. Several investigations (e.g. McBride, 1983; McClaran, 1988) have found some evidence that a tree once scarred is more easily scarred subsequently. Consequently, unscarred and scarred trees may have different potential for scarring and hence have different fire records. Also, the speed at which healing allows closure of the scar and the time between fires interact with the potential for scarring. Clearly a good understanding of the physical processes involved in fire scar formation would be useful. Unfortunately, at the present time this understanding is incomplete (Spalt and Reifsnyder, 1962; Hare, 1965a,b; Gill and Ashton, 1968; Vines, 1968; Gill, 1974; Tunstall et al., 1976).